- Home

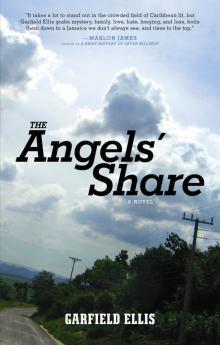

- Garfield Ellis

The Angels' Share

The Angels' Share Read online

Table of Contents

___________________

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

Twenty

Twenty-One

Twenty-Two

Twenty-Three

Twenty-Four

Twenty-Five

Twenty-Six

Twenty-Seven

Twenty-Eight

Twenty-Nine

Thirty

Thirty-One

E-Book Extras

A Note from the Author

Photos

Reading Group Guide

About Garfield Ellis

Copyright & Credits

About Akashic Books

For Garfield, my son;

it’s not just the experiences but the lessons we take from them.

ONE

It may be anywhere between four and five a.m. Monday morning. I am wide awake and panting. My girlfriend Audrey is grinding backward up against me ferociously.

This is her favorite position, this is her favorite time: on the still edge of morning, her body twisted slightly on its side, one leg wrapped back almost around my waist, a hand tight on my neck as I thrust deeply into her with long, strong, deliberate strokes.

She has been here since yesterday, using her marketing expertise to help me all day with my presentation, which is to be made to the board of directors later today. Last night I had been too tired to attend to her, and now she is intent on making up for the last three weeks.

And I don’t mind, for I can be greedy that way, myself . . . when I am in the mood.

So I am panting, grinding back, aiming along her heaving, moist crevices, so I may synchronize and glide true and deep with the thrusts she craves.

And then the phone rings, shattering the morning like a stone splintering a glass window. I freeze and everything in me grows cold and still. Phones do not ring innocently at five o’clock in the morning. They always bring bad news. So part of me is pausing because I am startled and the other part of me is hoping it will stop; as if by being quiet it will think I am not here and not ring again. I hold my breath, and even Audrey is momentarily paused against me.

The last time my phone rang at five a.m. it brought the news that my mother had taken a turn for the worse, giving me just sufficient time to race to the hospital and hold her hand for two hours before she died. Now this morning I am afraid of what news it may bring.

It stops, and then rings again; and I know I must answer, but Audrey is no longer paused; she begins to grind even more urgently against me—completing the penetration with a backward thrust.

Caught between the urgency of the ringing phone and the heat of a woman on the edge of orgasm, I feel the pressure of a slippery slope. But the decision is already made for me as I am already wilting away from responding to her. Disentangling from her requires more force than I expected, and as I reach for the phone, she shrugs away into the folds of the sheets with more anger than is necessary.

It is Una, my father’s wife, and her voice is heavy with tears and panic: “Your father is missing, and I don’t know where he is. And I know he is not with you.”

I feel the blood drain from my face, I feel an absence of strength, and breath rushes from my lungs as if I have just run ten miles.

“Everton, Everton!”

“What do you mean missing, Una, it is only five o’clock.”

“It was before that, but I never wanted to wake you up.”

“I spoke to him on the phone yesterday.”

“Yes! I did too.” She pauses. “I talked to him in the morning and then I got back and he is gone.”

“Got back from where?”

“I was at Holly’s for the weekend.”

Though I am sitting down, I am reaching with my hand to grip the sheets and steady myself. How do you respond to something like this? How do you respond? What do you say? How do you behave?

“He’s gone, Everton, he’s gone. And I don’t know where he is.” She is crying and her words are running into each other. I must calm her, I must calm myself.

“Una, you sure he is not in the back room sleeping or in the cellar or something?”

“He’s gone!” Angry now and screaming.

This is 2008 Jamaica; old people are burnt in their homes for no reason at all; stubborn old men are slaughtered by gunmen. Old people living alone in the middle of Hampshire have little to protect them . . . and now my father is missing. Jesus!

“Una, it’s okay, just slow down.”

There is a pause.

“Una, Una!” I am almost screaming now.

“Yes.”

“When did you miss him, Una?”

“I told you that already. I wasn’t here, I said, I was at your brother’s. His children were here for the summer. I took the children home. I stayed the weekend and when I came back, he was missing.”

“But he can’t just go missing so. Is the house ransacked, did someone break in?”

“He is gone to her! I know he’s not with you.”

“Una!”

“I don’t know, I don’t know.” She is getting incoherent and I sense a falling away, a wilting.

“Una!”

“You better come up here, Everton.”

“Una, don’t do anything. Lock all the doors. Do not do anything. I am coming up there right now.”

There is no lust left in this room. Audrey is already dressed. I did not notice her move, let alone find and put on her clothes.

“Where are you going?” My voice is close to a whisper.

“Where do you think?”

“You haven’t even bathed. You vexed about something.”

“I have water at home, and you are in a hurry. You have somewhere to go.”

“Yeah, but where you going?”

“I don’t believe you answered that.” She is collecting her things now, kicking her shoes together to step into them as she drops her earrings into her bag. “I don’t believe you answered that phone.”

“My father is missing. You heard the conversation.”

“You don’t even love your damn father.”

“What!”

“You don’t love me, okay? You don’t want me. You not interested in a relationship. You just love yourself. Don’t believe you answered it!”

“What? You hear what I just said?”

“You don’t even love your damn father!”

Is this the same woman who has been here with me since yesterday? The soft, sweet, intelligent girl, drawing lines through the outline of my PowerPoint presentation, giving me advice on how it should be shown for maximum effect? Audrey, snuggling up to me, making coffee when the night got cold, cooking dinner, and bringing wine for the evening meal? Audrey, showing patience, cuddling when I was too tired to even move—is this the soft, understanding Audrey, lying on my lap, listening while I pour out my soul to her, understanding and identifying with me, she having grown up even poorer without even knowing her father? Where did this person come from . . . and over a little sex?

“I had to answer the phone. My father is missing, okay? And you are angry about what, again?”

“Don’t even make this about the sex. Don’t even make this about your father. Okay? Don’t even go there.”

“Really! This is really the most ridiculous thing I have ever seen, okay? This is too much for me. It is Monday mo

rning. I have a presentation in a couple of hours, my father is missing, and he could be dead in a bush somewhere. And I am being chastised because I answered the phone, to this crisis, because you did not get an orgasm. And you want me to what? Say it’s not about the sex? How could this not be about the sex? How could it be about sex?”

She pauses halfway to the door and turns to me. In the soft light of the room, I can see the anger simmering in her eyes and beneath the softness of her face.

“Listen, Everton, you know and I know this relationship is not going anywhere. We live half an hour from each other; we work ten minutes away from each other. Yet I have not seen you in nearly a month. Last weekend it was your father, before that you got a new company to run, then last week you had to whip the company into shape. This weekend—presentation. And now you are going to Hampshire. Does that look like a relationship to you? Do you see me fitting in there?”

“But my father is missing.”

“Don’t!” She is so angry now it is almost as if she’s going to cry. “You don’t need a relationship. Or maybe you need one, but you don’t need me. In any event, I have to leave. I have to go to work, remember? This is not about your father, okay? You damn well know this is about you and your own selfishness.”

I do not chase after her as she leaves. I do not try to hold her back . . . well, not immediately, for I do not think she is serious. But now I hear the front door slam, and I am chasing down the stairs after her. I get as far as the kitchen when I hear her tires on the gravel of the driveway, and the gun of the engine as she speeds away.

I am confused, unsure, unable to focus. I try to make coffee, fill the kettle with water, switch it on, and sit at the counter wondering what to do.

Papers are scattered everywhere, just as we left them last night. The large yellow pad with all the notes I took down from her criticism is lying with the remote on the ground where we left it. Dazed, I glance around at the mess of paper she had pushed aside; the roll of taped-up leaves she made into a ball and threw, only to miss the rubbish can as she mimicked a basketball player; the smudge on the corner of the projector where she dabbed jelly in order to make me mad; the pencil shavings, the cork from a wine bottle, the remains of the ice cream on the counter where she drew her name. Everything connected, yet disconnected in its own way. Nothing making sense in and of itself—just like the words she uttered as her anger rose. You don’t love me . . . You only love yourself . . . You don’t even love your damn father!

I am suddenly struck by another strange reality. Your father is missing. I jump from my seat at the counter and run up the stairs, taking them two at a time. Hampshire! I must go to Hampshire. I must leave here now; I must go to Hampshire and find my father.

But I am overwhelmed by a strange instinct. Instead of running toward the bedroom to dress, I am being pulled by this strange instinct to the little bedroom I am planning to use as a library. Suddenly, I am rummaging through the old boxes I have stored there, first deliberately then frenziedly, digging among the confusion of old suitcases and boxes; tearing the cobwebs that ensnare me, filling my nostrils with dust; scattering papers, old books, clippings, yearbooks, magazines, graduation gowns; overturning cartons; scrabbling through books, desperately searching for a little old Bible my mother gave me a million memories ago.

Among its yellowing pages is a folded piece of paper I had torn from my high school notebook when I left home for college. The paper is so old the creases are stuck together and brown. The writing is faded but still legible. The heading jumps at me just as forcefully as the day I scribbled it there with an angry, uncertain, adolescent hand: Ten Questions for My Father.

I take the piece of paper and read the words over and over, each line, each question, even though they have been etched in my memory like a childhood nursery rhyme. I read them still and relive again in their fullest force the feelings that shaped them.

I don’t know why I have done this, don’t understand the emotions that drove me to this old Bible in this old box of memories. I can’t imagine the difference these words will make when I already know them by heart, and I have no reason to believe or expect that after twenty-five years the moment will finally present itself—and if it does, that I will have the courage to ask them.

Your father is missing.

Something about those desperate words has driven me here—to this room, to memories hidden by layers and layers of years.

Twenty-five years.

And now he is missing. I feel paralyzed by an odd fear—an odd notion that I may never see him again.

Ten Questions for My Father.

I must start moving. I must get to Hampshire and find him.

TWO

I am not a selfish man. I love much, much more than myself.

I love my father.

For here I am this morning, sandwiched between two trucks on the Flat Bridge, traffic backed up on both sides. It is seven o’clock and still I am not even halfway to Hampshire. And with every honk of an angry horn, and every stop and start and stutter of the vehicles in the line, every inching forward of the traffic, I feel my career disappearing slowly behind me. So how could I be a selfish man? How could I not love my father? I am sacrificing my day for him. I am sacrificing my presentation for him. I am sacrificing a board meeting for him. I am sacrificing my career for him.

I have sacrificed a woman for him.

Three years of back-and-forth, stopping and starting, stuttering, tied together by periods of intense passion, and tenderness beyond belief. Now this, out of nowhere: You just love yourself. Words coming from nowhere for reasons only God knows—You don’t love me—not making any sense at all.

And this damn ugly river sliding like a brown snake through the misting gorge that extends for miles on both sides of this slab of a bridge on which I crawl, still slithering down, slowly and menacingly. The land rising, one side green and lush, the other cavernous and bare, but both rising high—and a gorge through which the river and the road that tracks it share an uneasy alliance, slipping and sliding together like lovers entwined in some sensuous ritual—knowing, understanding, accepting that every now and then the river will gather its forces from way beyond, in the hills of St. Catherine, and thunder through it, taking everything in its wake, cutting off the north of the country from the south.

Where could he be? I have tried calling Una twice, but the phone rings out. Where could the old man be?

It is hard not to think bad thoughts. This is Jamaica, modern-day Jamaica, where it is so easy to get away with murder. Two months ago, in Manchester, a retired banker and his wife, a retired teacher, were bludgeoned to death and burned in their houses. They had lived there all their lives on a five-acre plot of land, farming goats in their retirement—murdered and burned alive. A month ago, another old man—who’d spent his life working in England, but having built a house here, returned to retire—was trailed by gunmen from the airport, robbed, bludgeoned, killed, then cast out on the street like a dog. And even now, in the news every day, old people, homeless people, emerging from the bushes and hills of Mandeville, dead, half-dead, discarded. Some wander into the sulfuric death of the bauxite red lakes, some are swept up from the streets of Montego Bay and dumped like garbage in the hills, in order to clean up for a tourist conference. It is a hard place to be old and retired or homeless.

Your father is missing . . . and I know he is not with you.

And now, this empty space, this phone ringing and ringing with no answer. As if he has dropped off some cliff. Missing?

What was the last thing I said to him? What was the last thing I saw of him? What did he look like, what did he want to do? Was he smiling? What did I say, what did I say? Later, old man, next week, I am coming for you next week. Was that the last thing—was later the last thing? Did I say later or did he say later? Was he smiling, was he sad?

Did I leave my old man sad? Did I say last weekend meaning yesterday, day before yesterday, when I was wrapped up in the a

rms of an ungrateful woman, working?

Where is he?

I can’t even see around the corner of this damn gorge, just the damn truck in front of me and the light blinking, indicating it is going slow as if everybody can’t see that. And everything shaded in mist. And trees hanging now on both sides of the gorge: breadfruit trees along the slopes, and small cultivation with no system to it; yam curling up the vines, corn, peas, vegetation up and down—dense. Even the light posts are laden with heavy vines so that one can hardly see them, just the hint of board in some places and the electricity wires sagging out like overweight clotheslines. And the people now, slipping up and down its side like ghosts coming into view as they hit the road while the mist stirs slightly and the day starts. They are moving among the trapped motorists, hawking mangoes and oranges and star apples and jackfruits, shoving them against the glass, pushing them through open windows as we slip uneasily from the Flat Bridge and onto the road.

The truck in front of me curves away, and for a minute I am pointing straight ahead across the water, and because of the curve of the road, it seems the trees on all sides have met and I am heading into a wall of trees with the water curling, a serpentine green from deep inside it. There is a stillness and a pause—a waiting—and everything green and still, and the mist rising, drifting from the water as if it is very cold in the green dark out there, and the sky barely showing above. And for a minute, everything is beautiful as I have never remembered; everything is cold, cozy and private, yet wild, like a soft wet Christmas morning.

This must be what he sees. This must be what makes him love this place so much.

For this is his place, this is his domain; the territory he supervised while he worked for the government; all the land that is fed and silted by this river, all the land that draws water from it, all the lands fed, silted, and served by the tributaries that feed it. Everything shooting out on every side of this curvaceous, cavernous, serpentine curl. From the hills of Harkers Hall through the plains of Riversdale, Knollis, and Tulloch in the east, to as far west as the orange groves of Linstead and Wakefield and the plains of Springvale made green by miles of cane fields.

The Angels' Share

The Angels' Share